What was the purpose of Roman forts and fortresses, and how were they organised?

Most of the soldiers stationed on the Wall, its outposts to the north, the Cumbrian Coastal system and indeed the hinterland were quartered in forts. Understanding the anatomy of forts is therefore vital to understanding how the Roman army of Britain worked.

What were they for?

Forget any preconceived notion based on medieval castles: of high walled citadels designed to withstand determined siege. The forts and fortresses of Roman Britain were not built with such concerns in mind. None of Rome’s British adversaries had the capacity to sustain a siege even if they could, briefly, marshal the forces necessary to confront Rome’s military might in the field.

Yet forts and fortresses were essential instruments in Rome’s conquest and control of Britain. In some respects they performed similar functions to towns, facilitating administrative control, and they should be understood as part of a wider discussion of urbanism. As we will see, they were home to a wide range of non-combatants.

But forts were also, as the archaeologist Professor Simon James puts it, ‘wolf cages’ designed to keep soldiers in order. Not all of Rome’s soldiers were willing. Contemporary documents from other provinces refer to desertion, to soldiers running riot, and less frequently but significantly, to mutinies by entire regiments.

Under Hadrian’s original scheme, the Wall included milecastles and turrets, but in a significant development (known to archaeologists as the ‘fort decision’) larger installations accommodating 400 to 1,000 soldiers were constructed. These forts were an essential part of Roman strategy, complementing a handful of outpost forts north of the Wall, as well as the large number of military bases to the south. Further south again were the great fortresses at York and Chester, capable of housing entire legions of 5,000 to 6,000 men.

Design and layout

While no two forts or fortresses were identical, they shared several key elements. Later in the course we will examine what life was like in the different parts of these complex settlements, but let us start with the basic layout.

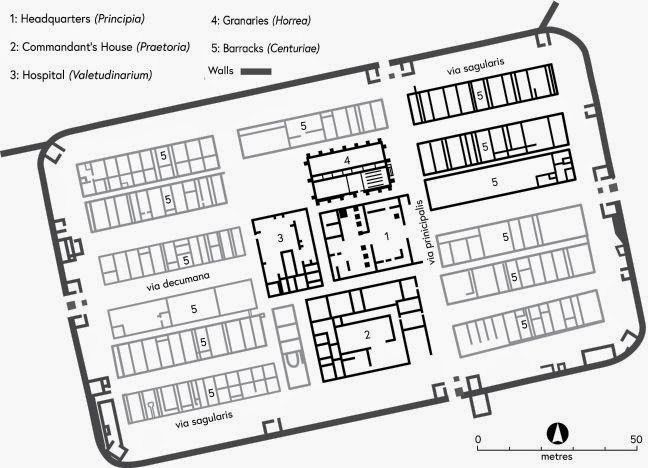

In our image above you can see a plan of the fort at Wallsend (Segedunum). Wallsend is important because:

- it was the fort at end of the curtain wall, where Hadrian’s Wall literally came to its end in the River Tyne

- it was the first fort where Newcastle archaeologists were able to produce a convincing plan of its earliest, Hadrianic phase

Evidence suggests Wallsend contained a cohort of approximately 500 men made up of a mixture of cavalry and infantry. Note the different elements in the plan – the classic playing card shape of the fort, its curved corners (a legacy from the older practice of making turf walls, despite sharp corners being easier to build in stone). As at most other forts, an extra-mural settlement and communal baths lay beyond the walls, and we will see those later, but for the moment our concern is what lay within.

As our image shows, the dominant type of building were the long thin barrack blocks.

Forts had at their centre a headquarters building (principia) consisting of a courtyard and covered hall (basilica). This building housed the regimental standard in a chapel, guarded 24 hours, which itself lay over the fort’s underground strong-room holding soldiers’ pay chests.

Adjacent to the principia lay the commanding officer’s house (praetorium) which followed the layout of a traditional Mediterranean style courtyard house, making few concessions to the climate! In keeping with Roman notions of work and leisure, the praetorium was both a place for the commanding officer (and family) to live and conduct official business.

The final element in the central range of the fort would have been the granaries (horrea), substantial buttressed buildings, capable of holding (amongst other things) enough grain for the soldiers’ needs for a year.

Sometimes as at Wallsend, we find other structures, such as a probable hospital (valetudinarium), made up of rooms around a small courtyard, and more rarely a covered training hall.

Below are two very different images of Roman military installations.

The first is a plan of the legionary fortress the Romans began constructing at Inchtuthil in Scotland in the AD 80s. It is clear that its construction was central to imperial plans to establish permanent military control there – but when other priorities intervened and soldiers were needed abroad, it was abandoned, and archaeologists inherited one of the most complete plans of a legionary fortress anywhere.

Our second picture shows Housesteads (Vercovicium), first excavated in the nineteenth century and most recently the site of another major Newcastle University excavation. It is one of the best known forts on the Wall and is commonly, and somewhat misleadingly, used as an example of a typical fort. The units stationed in and around it changed over time, but it is known to have contained an infantry regiment of about 800 soldiers during the second and third centuries AD.

No comments:

Post a Comment